Can You Add Two Registers Together

x86 Assembly Guide

Contents: Registers | Retentivity and Addressing | Instructions | Calling Convention

This is a version adapted by Quentin Carbonneaux from David Evans' original document. The syntax was changed from Intel to AT&T, the standard syntax on UNIX systems, and the HTML code was purified.

This guide describes the basics of 32-bit x86 assembly linguistic communication programming, roofing a small but useful subset of the bachelor instructions and assembler directives. There are several different associates languages for generating x86 machine lawmaking. The one we will use in CS421 is the GNU Assembler (gas) assembler. We will uses the standard AT&T syntax for writing x86 associates code.

The full x86 education set is large and complex (Intel's x86 instruction gear up manuals comprise over 2900 pages), and nosotros do not cover it all in this guide. For instance, at that place is a 16-flake subset of the x86 pedagogy set. Using the xvi-bit programming model can be quite complex. It has a segmented retentivity model, more restrictions on register usage, and and so on. In this guide, nosotros will limit our attention to more modernistic aspects of x86 programming, and delve into the instruction set simply in enough detail to get a bones feel for x86 programming.

Registers

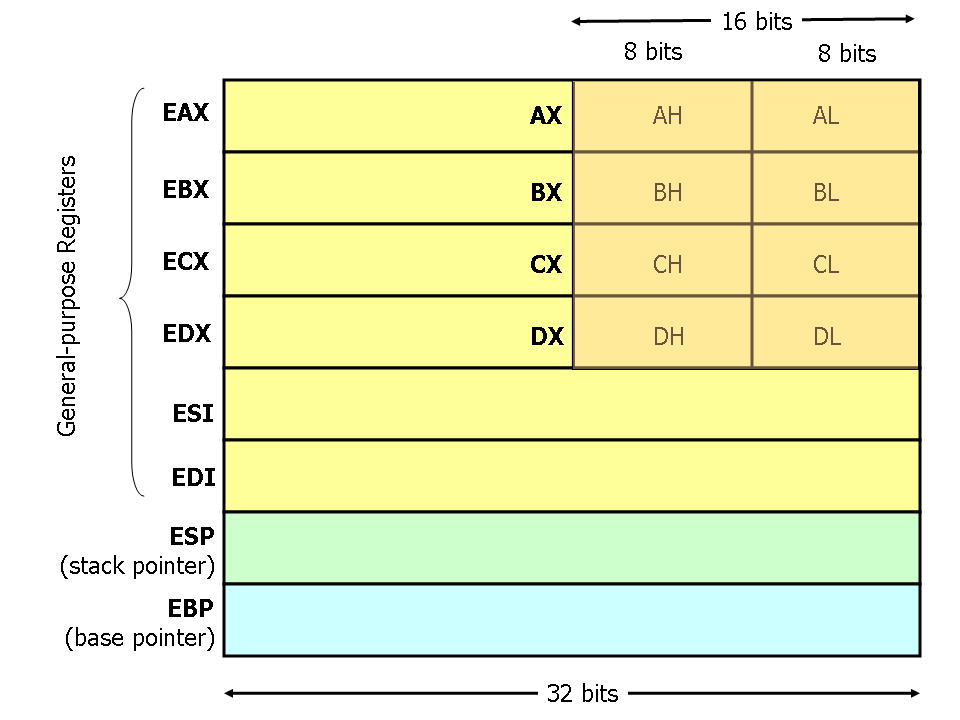

Modern (i.e 386 and beyond) x86 processors have eight 32-bit general purpose registers, as depicted in Figure 1. The register names are mostly historical. For instance, EAX used to be chosen the accumulator since it was used by a number of arithmetic operations, and ECX was known as the counter since information technology was used to concord a loop alphabetize. Whereas near of the registers have lost their special purposes in the mod instruction set, by convention, two are reserved for special purposes — the stack pointer (ESP) and the base pointer (EBP).

For the EAX, EBX, ECX, and EDX registers, subsections may be used. For example, the least pregnant ii bytes of EAX can exist treated as a 16-bit register called AX. The to the lowest degree significant byte of AX can exist used as a single 8-scrap register called AL, while the well-nigh significant byte of AX can be used equally a single eight-fleck register called AH. These names refer to the same physical annals. When a two-byte quantity is placed into DX, the update affects the value of DH, DL, and EDX. These sub-registers are mainly hold-overs from older, 16-fleck versions of the instruction set. However, they are sometimes convenient when dealing with information that are smaller than 32-bits (e.grand. ane-byte ASCII characters).

Figure 1. x86 Registers

Memory and Addressing Modes

Declaring Static Information Regions

You lot can declare static data regions (coordinating to global variables) in x86 associates using special assembler directives for this purpose. Information declarations should be preceded by the .data directive. Following this directive, the directives .byte, .short, and .long can be used to declare one, two, and four byte information locations, respectively. To refer to the address of the data created, we can characterization them. Labels are very useful and versatile in assembly, they give names to retentiveness locations that volition exist figured out later by the assembler or the linker. This is like to declaring variables by proper noun, just abides past some lower level rules. For case, locations declared in sequence will be located in retention next to one another.

Example declarations:

.information var: .byte 64 /* Declare a byte, referred to every bit location var, containing the value 64. */ .byte 10 /* Declare a byte with no label, containing the value ten. Its location is var + ane. */ x: .short 42 /* Declare a 2-byte value initialized to 42, referred to as location 10. */ y: .long 30000 /* Declare a 4-byte value, referred to equally location y, initialized to 30000. */

Dissimilar in high level languages where arrays tin can have many dimensions and are accessed past indices, arrays in x86 associates language are simply a number of cells located contiguously in memory. An array can exist declared by but listing the values, as in the showtime case below. For the special case of an array of bytes, cord literals can be used. In instance a large expanse of memory is filled with zeroes the .zero directive tin be used.

Some examples:

s: .long i, 2, 3 /* Declare iii four-byte values, initialized to one, 2, and 3.

The value at location s + 8 will be iii. */barr: .zero x /* Declare x bytes starting at location barr, initialized to 0. */ str: .string "how-do-you-do" /* Declare 6 bytes starting at the address str initialized to

the ASCII character values for hello followed past a nul (0) byte. */

Addressing Retentiveness

Modern x86-compatible processors are capable of addressing up to 232 bytes of memory: memory addresses are 32-$.25 wide. In the examples above, where nosotros used labels to refer to retentivity regions, these labels are actually replaced by the assembler with 32-bit quantities that specify addresses in memory. In addition to supporting referring to retention regions by labels (i.east. constant values), the x86 provides a flexible scheme for computing and referring to retentiveness addresses: up to two of the 32-bit registers and a 32-bit signed abiding can exist added together to compute a memory accost. One of the registers can be optionally pre-multiplied by 2, 4, or 8.

The addressing modes tin exist used with many x86 instructions (we'll describe them in the next section). Here we illustrate some examples using the mov instruction that moves information betwixt registers and retentiveness. This instruction has 2 operands: the first is the source and the 2nd specifies the destination.

Some examples of mov instructions using address computations are:

mov (%ebx), %eax /* Load 4 bytes from the retentiveness address in EBX into EAX. */ mov %ebx, var(,1) /* Movement the contents of EBX into the 4 bytes at memory address var.

(Note, var is a 32-bit abiding). */mov -4(%esi), %eax /* Movement 4 bytes at retentiveness address ESI + (-iv) into EAX. */ mov %cl, (%esi,%eax,ane) /* Move the contents of CL into the byte at accost ESI+EAX. */ mov (%esi,%ebx,4), %edx /* Movement the iv bytes of data at address ESI+4*EBX into EDX. */

Some examples of invalid address calculations include:

mov (%ebx,%ecx,-1), %eax /* Can only add register values. */ mov %ebx, (%eax,%esi,%edi,ane) /* At most ii registers in accost ciphering. */

Performance Suffixes

In general, the intended size of the of the data detail at a given memory address tin can be inferred from the assembly code instruction in which it is referenced. For example, in all of the above instructions, the size of the memory regions could be inferred from the size of the annals operand. When nosotros were loading a 32-scrap annals, the assembler could infer that the region of memory we were referring to was 4 bytes broad. When we were storing the value of a ane byte annals to memory, the assembler could infer that nosotros wanted the address to refer to a single byte in memory.

However, in some cases the size of a referred-to retentivity region is ambiguous. Consider the instruction mov $2, (%ebx). Should this educational activity move the value two into the single byte at address EBX? Perhaps it should movement the 32-chip integer representation of 2 into the 4-bytes starting at address EBX. Since either is a valid possible interpretation, the assembler must be explicitly directed as to which is correct. The size prefixes b, west, and l serve this purpose, indicating sizes of ane, 2, and iv bytes respectively.

For case:

movb $two, (%ebx) /* Motility ii into the single byte at the address stored in EBX. */ movw $2, (%ebx) /* Move the 16-bit integer representation of 2 into the 2 bytes starting at the address in EBX. */ movl $2, (%ebx) /* Motility the 32-bit integer representation of 2 into the 4 bytes starting at the address in EBX. */

Instructions

Machine instructions generally fall into three categories: data motion, arithmetics/logic, and control-flow. In this section, nosotros will expect at important examples of x86 instructions from each category. This section should not be considered an exhaustive list of x86 instructions, only rather a useful subset. For a complete list, see Intel's teaching gear up reference.

Nosotros use the following notation:

<reg32> Any 32-bit register (%eax, %ebx, %ecx, %edx, %esi, %edi, %esp, or %ebp) <reg16> Any sixteen-bit annals (%ax, %bx, %cx, or %dx) <reg8> Whatever 8-flake register (%ah, %bh, %ch, %dh, %al, %bl, %cl, or %dl) <reg> Any register <mem> A retention address (east.g., (%eax), four+var(,ane), or (%eax,%ebx,one)) <con32> Any 32-chip immediate <con16> Any 16-bit firsthand <con8> Any 8-chip firsthand <con> Whatever 8-, 16-, or 32-flake firsthand

In assembly language, all the labels and numeric constants used as firsthand operands (i.e. not in an address calculation like three(%eax,%ebx,8)) are always prefixed by a dollar sign. When needed, hexadecimal notation can exist used with the 0x prefix (e.thou. $0xABC). Without the prefix, numbers are interpreted in the decimal basis.

Data Motility Instructions

mov — Move

The mov teaching copies the data item referred to by its first operand (i.e. register contents, retentiveness contents, or a constant value) into the location referred to by its 2nd operand (i.e. a register or memory). While annals-to-annals moves are possible, straight memory-to-memory moves are not. In cases where memory transfers are desired, the source memory contents must outset be loaded into a register, then can be stored to the destination retention accost.Syntax

mov <reg>, <reg>

mov <reg>, <mem>

mov <mem>, <reg>

mov <con>, <reg>

mov <con>, <mem>

Examples

mov %ebx, %eax — copy the value in EBX into EAX

movb $five, var(,1) — store the value 5 into the byte at location var

button — Push on stack

The button instruction places its operand onto the top of the hardware supported stack in memory. Specifically, push first decrements ESP by four, then places its operand into the contents of the 32-bit location at accost (%esp). ESP (the stack arrow) is decremented past push since the x86 stack grows down — i.e. the stack grows from high addresses to lower addresses.Syntax

push <reg32>

button <mem>

button <con32>Examples

button %eax — button eax on the stack

push var(,1) — button the 4 bytes at address var onto the stack

pop — Popular from stack

The pop didactics removes the iv-byte data element from the top of the hardware-supported stack into the specified operand (i.eastward. register or retention location). It first moves the four bytes located at retentiveness location (%esp) into the specified register or memory location, and then increments ESP by iv.Syntax

Examples

pop <reg32>

pop <mem>

pop %edi — pop the top element of the stack into EDI.

popular (%ebx) — popular the top element of the stack into retentiveness at the four bytes starting at location EBX.

lea — Load constructive address

The lea pedagogy places the address specified by its first operand into the register specified by its second operand. Note, the contents of the memory location are not loaded, only the effective address is computed and placed into the annals. This is useful for obtaining a pointer into a memory region or to perform uncomplicated arithmetics operations.Syntax

lea <mem>, <reg32>

Examples

lea (%ebx,%esi,eight), %edi — the quantity EBX+8*ESI is placed in EDI.

lea val(,one), %eax — the value val is placed in EAX.

Arithmetic and Logic Instructions

add together — Integer addition

The add together pedagogy adds together its ii operands, storing the issue in its second operand. Note, whereas both operands may be registers, at most one operand may exist a memory location.Syntax

add together <reg>, <reg>

add together <mem>, <reg>

add together <reg>, <mem>

add <con>, <reg>

add <con>, <mem>

Examples

add $ten, %eax — EAX is set to EAX + ten

addb $10, (%eax) — add 10 to the unmarried byte stored at memory address stored in EAX

sub — Integer subtraction

The sub instruction stores in the value of its 2d operand the result of subtracting the value of its first operand from the value of its second operand. As with add, whereas both operands may be registers, at most one operand may exist a memory location.Syntax

sub <reg>, <reg>

sub <mem>, <reg>

sub <reg>, <mem>

sub <con>, <reg>

sub <con>, <mem>

Examples

sub %ah, %al — AL is set to AL - AH

sub $216, %eax — subtract 216 from the value stored in EAX

inc, dec — Increment, Decrement

The inc education increments the contents of its operand past one. The dec teaching decrements the contents of its operand by one.Syntax

inc <reg>

inc <mem>

dec <reg>

dec <mem>Examples

dec %eax — decrease one from the contents of EAX

incl var(,1) — add one to the 32-chip integer stored at location var

imul — Integer multiplication

The imul instruction has two bones formats: two-operand (first two syntax listings above) and three-operand (final two syntax listings above).The 2-operand form multiplies its ii operands together and stores the upshot in the 2nd operand. The upshot (i.e. second) operand must exist a register.

The 3 operand form multiplies its second and third operands together and stores the result in its last operand. Again, the result operand must exist a register. Furthermore, the first operand is restricted to beingness a constant value.

Syntax

imul <reg32>, <reg32>

imul <mem>, <reg32>

imul <con>, <reg32>, <reg32>

imul <con>, <mem>, <reg32>Examples

imul (%ebx), %eax — multiply the contents of EAX by the 32-bit contents of the retentivity at location EBX. Store the event in EAX.

imul $25, %edi, %esi — ESI is set to EDI * 25

idiv — Integer division

The idiv didactics divides the contents of the 64 bit integer EDX:EAX (constructed by viewing EDX as the virtually significant four bytes and EAX equally the least pregnant four bytes) by the specified operand value. The caliber result of the division is stored into EAX, while the balance is placed in EDX.Syntax

idiv <reg32>

idiv <mem>Examples

idiv %ebx — divide the contents of EDX:EAX by the contents of EBX. Place the quotient in EAX and the residue in EDX.

idivw (%ebx) — divide the contents of EDX:EAS past the 32-bit value stored at the memory location in EBX. Place the quotient in EAX and the remainder in EDX.

and, or, xor — Bitwise logical and, or, and exclusive or

These instructions perform the specified logical operation (logical bitwise and, or, and exclusive or, respectively) on their operands, placing the result in the start operand location.Syntax

and <reg>, <reg>

and <mem>, <reg>

and <reg>, <mem>

and <con>, <reg>

and <con>, <mem>

or <reg>, <reg>

or <mem>, <reg>

or <reg>, <mem>

or <con>, <reg>

or <con>, <mem>

xor <reg>, <reg>

xor <mem>, <reg>

xor <reg>, <mem>

xor <con>, <reg>

xor <con>, <mem>

Examples

and $0x0f, %eax — articulate all but the last 4 bits of EAX.

xor %edx, %edx — set the contents of EDX to nil.

not — Bitwise logical non

Logically negates the operand contents (that is, flips all bit values in the operand).Syntax

not <reg>

not <mem>Case

not %eax — flip all the bits of EAX

neg — Negate

Performs the two's complement negation of the operand contents.Syntax

neg <reg>

neg <mem>Instance

neg %eax — EAX is set to (- EAX)

shl, shr — Shift left and correct

These instructions shift the bits in their beginning operand's contents left and right, padding the resulting empty fleck positions with zeros. The shifted operand can be shifted up to 31 places. The number of bits to shift is specified by the second operand, which can be either an eight-bit constant or the register CL. In either instance, shifts counts of greater then 31 are performed modulo 32.Syntax

shl <con8>, <reg>

shl <con8>, <mem>

shl %cl, <reg>

shl %cl, <mem>shr <con8>, <reg>

shr <con8>, <mem>

shr %cl, <reg>

shr %cl, <mem>Examples

shl $ane, eax — Multiply the value of EAX past two (if the well-nigh significant chip is 0)

shr %cl, %ebx — Store in EBX the floor of result of dividing the value of EBX by 2 northward where n is the value in CL. Circumspection: for negative integers, it is unlike from the C semantics of division!

Command Flow Instructions

The x86 processor maintains an pedagogy arrow (EIP) register that is a 32-flake value indicating the location in retentiveness where the current educational activity starts. Usually, it increments to point to the side by side instruction in retentiveness begins afterward execution an didactics. The EIP register cannot exist manipulated directly, but is updated implicitly by provided control flow instructions.

We employ the notation <label> to refer to labeled locations in the program text. Labels can be inserted anywhere in x86 assembly code text by inbound a characterization proper noun followed past a colon. For example,

mov eight(%ebp), %esi brainstorm: xor %ecx, %ecx mov (%esi), %eax

The second educational activity in this code fragment is labeled begin. Elsewhere in the code, we can refer to the memory location that this instruction is located at in memory using the more than user-friendly symbolic proper noun begin. This label is just a convenient way of expressing the location instead of its 32-flake value.

jmp — Jump

Transfers program control menstruation to the instruction at the memory location indicated by the operand.Syntax

jmp <characterization>Example

jmp begin — Spring to the educational activity labeled begin.

jcondition — Provisional jump

These instructions are conditional jumps that are based on the status of a set of condition codes that are stored in a special annals called the car status give-and-take. The contents of the car condition word include information virtually the last arithmetics performance performed. For instance, one bit of this word indicates if the concluding result was zippo. Another indicates if the concluding result was negative. Based on these condition codes, a number of conditional jumps can be performed. For example, the jz didactics performs a jump to the specified operand label if the result of the terminal arithmetic operation was zero. Otherwise, control gain to the adjacent instruction in sequence.A number of the provisional branches are given names that are intuitively based on the terminal operation performed existence a special compare instruction, cmp (run across below). For example, provisional branches such as jle and jne are based on first performing a cmp operation on the desired operands.

Syntax

je <characterization> (jump when equal)

jne <label> (spring when not equal)

jz <characterization> (jump when last result was zero)

jg <label> (spring when greater than)

jge <label> (leap when greater than or equal to)

jl <characterization> (spring when less than)

jle <characterization> (jump when less than or equal to)Example

cmp %ebx, %eax jle washedIf the contents of EAX are less than or equal to the contents of EBX, jump to the label done. Otherwise, continue to the next pedagogy.

cmp — Compare

Compare the values of the two specified operands, setting the condition codes in the machine status word appropriately. This teaching is equivalent to the sub instruction, except the issue of the subtraction is discarded instead of replacing the first operand.Syntax

cmp <reg>, <reg>

cmp <mem>, <reg>

cmp <reg>, <mem>

cmp <con>, <reg>Case

cmpb $x, (%ebx)

jeq loopIf the byte stored at the memory location in EBX is equal to the integer abiding 10, leap to the location labeled loop.

call, ret — Subroutine call and render

These instructions implement a subroutine telephone call and return. The telephone call instruction first pushes the current lawmaking location onto the hardware supported stack in memory (see the push education for details), and then performs an unconditional jump to the code location indicated past the label operand. Unlike the unproblematic jump instructions, the call didactics saves the location to return to when the subroutine completes.The ret teaching implements a subroutine return machinery. This instruction first pops a code location off the hardware supported in-memory stack (come across the pop instruction for details). It then performs an unconditional jump to the retrieved code location.

Syntax

call <characterization>

ret

Calling Convention

To allow carve up programmers to share lawmaking and develop libraries for employ by many programs, and to simplify the use of subroutines in full general, programmers typically prefer a common calling convention. The calling convention is a protocol near how to call and render from routines. For example, given a prepare of calling convention rules, a programmer need not examine the definition of a subroutine to determine how parameters should be passed to that subroutine. Furthermore, given a set of calling convention rules, high-level linguistic communication compilers tin exist made to follow the rules, thus allowing hand-coded assembly language routines and loftier-level language routines to telephone call i another.

In practice, many calling conventions are possible. We will describe the widely used C linguistic communication calling convention. Following this convention will let you to write assembly language subroutines that are safely callable from C (and C++) lawmaking, and volition as well enable you to telephone call C library functions from your associates language lawmaking.

The C calling convention is based heavily on the use of the hardware-supported stack. It is based on the push, popular, telephone call, and ret instructions. Subroutine parameters are passed on the stack. Registers are saved on the stack, and local variables used by subroutines are placed in memory on the stack. The vast majority of high-level procedural languages implemented on most processors have used like calling conventions.

The calling convention is broken into two sets of rules. The offset set up of rules is employed by the caller of the subroutine, and the second prepare of rules is observed by the writer of the subroutine (the callee). It should be emphasized that mistakes in the observance of these rules speedily result in fatal program errors since the stack volition be left in an inconsistent state; thus meticulous care should be used when implementing the call convention in your own subroutines.

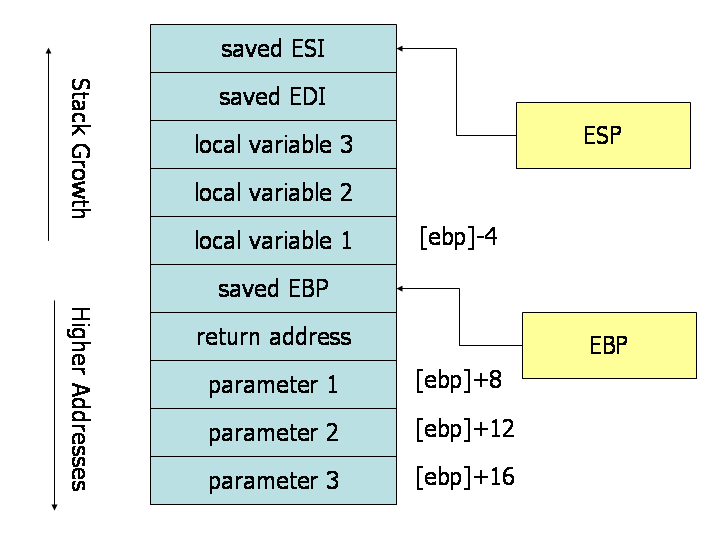

Stack during Subroutine Call

[Thanks to James Peterson for finding and fixing the bug in the original version of this figure!]

A expert fashion to visualize the functioning of the calling convention is to draw the contents of the nearby region of the stack during subroutine execution. The paradigm above depicts the contents of the stack during the execution of a subroutine with three parameters and three local variables. The cells depicted in the stack are 32-bit wide memory locations, thus the memory addresses of the cells are 4 bytes autonomously. The beginning parameter resides at an outset of 8 bytes from the base pointer. Above the parameters on the stack (and beneath the base pointer), the phone call instruction placed the return address, thus leading to an extra iv bytes of offset from the base of operations pointer to the start parameter. When the ret instruction is used to return from the subroutine, information technology volition jump to the return accost stored on the stack.

Caller Rules

To make a subrouting call, the caller should:

- Before calling a subroutine, the caller should save the contents of certain registers that are designated caller-saved. The caller-saved registers are EAX, ECX, EDX. Since the chosen subroutine is allowed to modify these registers, if the caller relies on their values after the subroutine returns, the caller must push the values in these registers onto the stack (then they can be restore after the subroutine returns.

- To pass parameters to the subroutine, push them onto the stack earlier the call. The parameters should exist pushed in inverted order (i.eastward. last parameter outset). Since the stack grows down, the get-go parameter volition be stored at the lowest address (this inversion of parameters was historically used to allow functions to be passed a variable number of parameters).

- To telephone call the subroutine, use the call instruction. This instruction places the return address on meridian of the parameters on the stack, and branches to the subroutine lawmaking. This invokes the subroutine, which should follow the callee rules below.

After the subroutine returns (immediately post-obit the phone call educational activity), the caller can expect to notice the return value of the subroutine in the annals EAX. To restore the machine state, the caller should:

- Remove the parameters from stack. This restores the stack to its country earlier the call was performed.

- Restore the contents of caller-saved registers (EAX, ECX, EDX) by popping them off of the stack. The caller tin assume that no other registers were modified past the subroutine.

Example

The lawmaking below shows a function call that follows the caller rules. The caller is calling a function myFunc that takes three integer parameters. Kickoff parameter is in EAX, the second parameter is the constant 216; the third parameter is in the memory location stored in EBX.

push (%ebx) /* Button final parameter first */ push $216 /* Push the second parameter */ push button %eax /* Push kickoff parameter terminal */ telephone call myFunc /* Phone call the part (assume C naming) */ add $12, %esp

Note that afterwards the phone call returns, the caller cleans up the stack using the add instruction. We take 12 bytes (three parameters * 4 bytes each) on the stack, and the stack grows downwards. Thus, to get rid of the parameters, nosotros tin simply add 12 to the stack pointer.

The result produced by myFunc is now bachelor for employ in the register EAX. The values of the caller-saved registers (ECX and EDX), may have been changed. If the caller uses them subsequently the call, it would have needed to salvage them on the stack before the call and restore them later information technology.

Callee Rules

The definition of the subroutine should adhere to the following rules at the kickoff of the subroutine:

- Push the value of EBP onto the stack, and then copy the value of ESP into EBP using the following instructions:

push %ebp mov %esp, %ebp

This initial action maintains the base pointer, EBP. The base pointer is used by convention as a indicate of reference for finding parameters and local variables on the stack. When a subroutine is executing, the base pointer holds a re-create of the stack pointer value from when the subroutine started executing. Parameters and local variables will always be located at known, constant offsets away from the base arrow value. Nosotros push the old base pointer value at the beginning of the subroutine so that we can later restore the appropriate base pointer value for the caller when the subroutine returns. Call up, the caller is not expecting the subroutine to alter the value of the base of operations pointer. Nosotros then motility the stack pointer into EBP to obtain our point of reference for accessing parameters and local variables. - Next, allocate local variables by making infinite on the stack. Recall, the stack grows down, so to make space on the peak of the stack, the stack pointer should be decremented. The amount by which the stack arrow is decremented depends on the number and size of local variables needed. For example, if three local integers (4 bytes each) were required, the stack arrow would need to be decremented by 12 to make space for these local variables (i.due east., sub $12, %esp). Every bit with parameters, local variables will exist located at known offsets from the base pointer.

- Side by side, salvage the values of the callee-saved registers that will be used by the function. To salvage registers, push them onto the stack. The callee-saved registers are EBX, EDI, and ESI (ESP and EBP will besides be preserved past the calling convention, but need not exist pushed on the stack during this step).

After these three actions are performed, the body of the subroutine may proceed. When the subroutine is returns, it must follow these steps:

- Leave the render value in EAX.

- Restore the former values of any callee-saved registers (EDI and ESI) that were modified. The register contents are restored past popping them from the stack. The registers should be popped in the inverse society that they were pushed.

- Deallocate local variables. The obvious way to do this might be to add the appropriate value to the stack pointer (since the infinite was allocated by subtracting the needed amount from the stack pointer). In practice, a less error-prone way to deallocate the variables is to move the value in the base pointer into the stack pointer: mov %ebp, %esp. This works considering the base of operations pointer always contains the value that the stack pointer contained immediately prior to the allocation of the local variables.

- Immediately before returning, restore the caller's base pointer value by popping EBP off the stack. Call up that the first thing nosotros did on entry to the subroutine was to push the base pointer to save its old value.

- Finally, render to the caller by executing a ret didactics. This educational activity will find and remove the appropriate return address from the stack.

Notation that the callee's rules fall cleanly into two halves that are basically mirror images of one another. The first half of the rules apply to the showtime of the function, and are unremarkably said to ascertain the prologue to the part. The latter half of the rules apply to the end of the function, and are thus commonly said to define the epilogue of the office.

Example

Here is an example office definition that follows the callee rules:

/* Kickoff the code department */ .text /* Ascertain myFunc as a global (exported) function. */ .globl myFunc .type myFunc, @office myFunc: /* Subroutine Prologue */ push button %ebp /* Save the sometime base arrow value. */ mov %esp, %ebp /* Set up the new base arrow value. */ sub $four, %esp /* Make room for one 4-byte local variable. */ push button %edi /* Save the values of registers that the function */ push %esi /* will modify. This function uses EDI and ESI. */ /* (no need to salve EBX, EBP, or ESP) */ /* Subroutine Body */ mov eight(%ebp), %eax /* Move value of parameter ane into EAX. */ mov 12(%ebp), %esi /* Motility value of parameter two into ESI. */ mov 16(%ebp), %edi /* Move value of parameter three into EDI. */ mov %edi, -4(%ebp) /* Move EDI into the local variable. */ add %esi, -4(%ebp) /* Add ESI into the local variable. */ add -iv(%ebp), %eax /* Add the contents of the local variable */ /* into EAX (final result). */ /* Subroutine Epilogue */ pop %esi /* Recover register values. */ pop %edi mov %ebp, %esp /* Deallocate the local variable. */ pop %ebp /* Restore the caller's base pointer value. */ ret

The subroutine prologue performs the standard actions of saving a snapshot of the stack pointer in EBP (the base of operations pointer), allocating local variables past decrementing the stack arrow, and saving register values on the stack.

In the body of the subroutine we tin see the utilize of the base of operations pointer. Both parameters and local variables are located at abiding offsets from the base pointer for the elapsing of the subroutines execution. In detail, we notice that since parameters were placed onto the stack before the subroutine was called, they are always located below the base pointer (i.due east. at higher addresses) on the stack. The commencement parameter to the subroutine can always be found at memory location (EBP+8), the second at (EBP+12), the 3rd at (EBP+16). Similarly, since local variables are allocated afterward the base pointer is prepare, they always reside higher up the base pointer (i.e. at lower addresses) on the stack. In particular, the first local variable is always located at (EBP-four), the second at (EBP-viii), and so on. This conventional employ of the base pointer allows us to quickly identify the use of local variables and parameters within a office torso.

The function epilogue is basically a mirror image of the function prologue. The caller's register values are recovered from the stack, the local variables are deallocated by resetting the stack arrow, the caller's base arrow value is recovered, and the ret didactics is used to return to the appropriate code location in the caller.

Credits: This guide was originally created by Adam Ferrari many years ago,

and since updated by Alan Batson, Mike Lack, and Anita Jones.

It was revised for 216 Spring 2006 past David Evans.

Information technology was finally modified by Quentin Carbonneaux to use the AT&T syntax for Yale'south CS421.

Can You Add Two Registers Together,

Source: https://flint.cs.yale.edu/cs421/papers/x86-asm/asm.html

Posted by: gentileannatimar.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Can You Add Two Registers Together"

Post a Comment